Remembering Veterans, Past, Present and Future

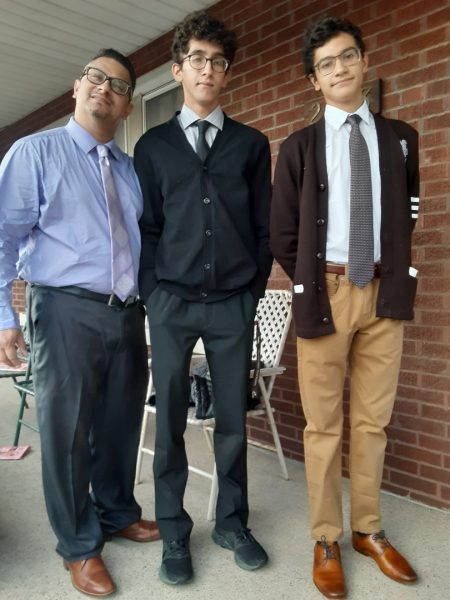

![Photograph of U.S. army Lt. Robert J. Perry (left) while he stands near an unidentified soldier standing on a dock along a body of water in Europe during WWII (undated) [Photograph taken or collected by Pleasants during his service in WWII]](https://mccaravan.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/PictureOfSoldiers-2.jpg)

State Archives of North Carolina Raleigh

Photograph of U.S. army Lt. Robert J. Perry (left) while he stands near an unidentified soldier standing on a dock along a body of water in Europe during WWII (undated) [Photograph taken or collected by Pleasants during his service in WWII]

Some return to be remembered, some return to be forgotten.

This November we remember our veterans who have fought courageously for our country. Veterans Day was established under President Woodrow Wilson. It was originally known as “Armistice Day,” a holiday enacted to honor the end of World War I. Congress amended the name to Veterans Day. Public opinion regarding veterans and the role they play in society is generally positive, but not all veterans have been treated in a way that shows appreciation after the fighting is over.

Overall, WWII veterans returned home to a nation that was grateful for their service. Yet many Latino and African American veterans, despite their wartime service, were not always extended acceptance and inclusion in various communities. Minority veterans may have received honor and respect for their military service; it’s estimated that 11 Mexican Americans received the Medal of Honor for the Bataan Death March, but were not respected as people. Roughly 500,000 Mexican Americans fought in WWII, with eleven of them receiving the Medal of Honor for the Bataan Death March alone, and Latinos fought in American wars as far back as the American Revolution. Despite this service, Latino WWII veterans were denied everyday opportunities when they came back home such as having a meal in a cafe or being provided regular funeral services. African American service members experienced segregation while serving, being confined to all-black units. Black soldiers were not integrated with their fellow American troops until the Korean War in 1950. When they returned home they continued to experience mistreatment even though they risked their lives for the country.

According to Ira Katznelson’s book When Affirmative Action Was White, African American vets were treated poorly even though they risked their lives. Katznelson tells the story of twenty-six-year-old John Hope Franklin, an African American man seeking to enlist in the military during the Second World War. He offered to participate in small tasks like handling paperwork and operating simple business machines because there was a shortage of personnel in the Navy. He was denied this opportunity due to his race. He stated, “The United States, however much it was devoted to protecting the freedoms and rights of Europeans, had no respect for me, no interest in my well-being and not even a desire to utilize my services.”

Another book that describes the segregation and discrimination of black vets is “The Color of Law” By Richard Rothstein. Routhstein describes the policies of the Housing Administration and Veterans Administration, both organizations refusing to insure mortgages for African Americans in designated white neighborhoods. Not even whites were insured mortgages in a mostly black neighborhood.

The Veterans Administration known today as Veterans Affairs has been plagued with numerous problems for years. Reports on the VA consist of inadequate health care services, leadership positions never being held down, and a massive backlog of unanswered benefits claims. According to a 2020 study by OutVets, approximately 400,000 veterans have been wrongly denied health care. As of now, there are over 1.4 million veterans at risk of becoming homeless due to the careless decision-making of the VA.

In 2019 the VA released the “Mission Act” to improve the accessibility of veteran services and the quality of healthcare. When it was rolled out it had four major problems. The first was the rushed development of the Mission Act. Secondly, the Mission Act requires that veterans live within a forty-mile radius from their local VA facility to receive services, or they must wait on a list for over thirty days. The VA must have this information to file progress reports on the veteran. This reporting is flawed because the administration has no idea what the financial aspect of an individual veteran looks like, let alone provide help with the finances of a veteran who needs to move to be closer to the VA. Thirdly the Mission Act is extremely complex considering the requirements are linked to non-VA programs. At the time the Choice Program became law the VA had several programs, each with its own eligibility conditions making it confusing for veterans trying to sign up. Finally, the lack of guidance for the project really affected its launch. This resulted in long wait times for veterans to be informed of approval to join the Mission Act causing medical billing confusion resulting in financial problems and debt for veterans. The Mission Act had a goal of trying to deliver the best quality of help to veterans when ultimately they failed.

The future of the VA claims to transform, simplify, empower and modernize. This remains to be seen. Even though veterans are celebrated on this special holiday it is important to remember the individual struggles experienced by veterans. Whether it’s racial discrimination, mental health conditions, or financial struggles as a society the goal is to remember and care for veterans as they cared for this great nation.